Xu Yang & Victoria Cantons: A Studio, A Shared Life

Tucked into a quiet corner of Chelsea, London, the shared studio of artists Xu Yang (MA, RCA 2020) and Victoria Cantons (MFA, Slade 2021) hums with creativity, mutual respect, and deep emotional resonance. As a couple in both life and art, they blur the boundaries between the personal and professional, offering a rare and intimate model of collaborative artistic practice.

On a visit to their studio, they welcomed us into their world—a space of open dialogue, shared resources, and distinct but harmoniously intertwined artistic identities.

Two Artists, One Studio

“We are each other’s first audience in the studio,” Victoria explains. “And a couple outside the studio. We are together 24/7.”

The dynamic between Xu Yang and Victoria Cantons is grounded in support, curiosity, and critique. They offer feedback on each other’s work, share collectors and galleries, and exchange ideas constantly. “We always open the door to the other,” says Victoria. “Some collectors really like the shared narrative we have.”

Their partnership has been evolving for eight years now, and this shared rhythm—of space, dialogue, and mutual discovery—forms a crucial part of their artistic process. “We share our research,” adds Yang. “It’s a constant collaboration.”

Credit: https://cedricbardawil.com/vystudio21/

Xu Yang: The Self as Subject

Xu Yang’s practice is rooted in the self—but not in isolation. Instead, she uses herself as a mirror, a model, a method of reflection. “I don’t know anyone as well as I know myself,” she says, aligning herself with the tradition of artists like Frida Kahlo, who used the self-portrait as both a confession and a declaration.

Her approach to femininity is unforced. “It just filters in,” she explains. “It’s not conscious—it just happens.” Growing up in China, she would draw quietly in the corner of her mother’s shop. “They wouldn’t believe she was the boss,” Yang remembers. That subtle cultural dismissal left an impression. Her mother’s advice—be independent, do what you like, and don’t care what people say—echoes today in Yang’s insistence on self-expression.

Her fascination with Rococo aesthetics—voluminous gowns, elaborate wigs, and layers of artifice—emerged after moving to the UK. In Rococo, she found not frivolity but freedom. “Those women used dresses and wigs to express themselves—opinions they couldn’t say out loud.” In contrast to the “ugly uniforms” of her youth, these ornate garments represented personality, defiance, and identity. “Rococo is the literal opposite,” she says. “And gender is performative,” referencing theorist Judith Butler. In Yang’s work, what you wear is never just decoration—it’s a declaration.

A Wonder to Behold (After Velázquez), 2024 by Xu Yang

Victoria Cantons: Portraits and the Politics of Visibility

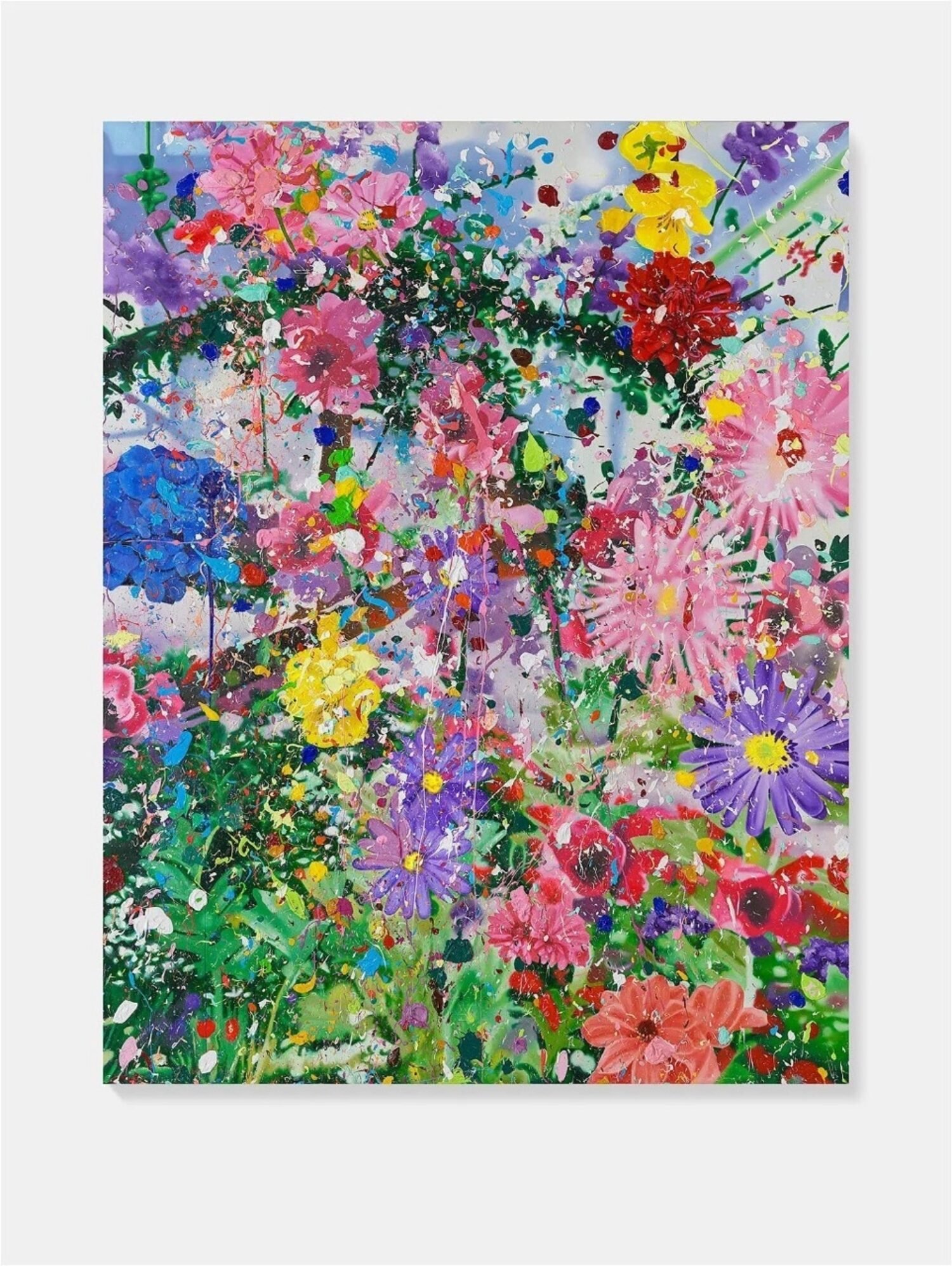

For Victoria, painting began as a way to make sense of her dual gendered life before transitioning at 39. “When I committed to art, it was about making sense of the world and my place in it,” she shares. “I used what was familiar around me.” Flowers, for instance—deeply symbolic in her work—are rooted in personal memory. “My mother had green fingers, especially with roses. Flowers are a symbolic form, representing emotion, declarations of love. They’re cyclical and ephemeral—just like us.”

While femininity is present in her work, it’s not its focal point. “It’s less about feminism and more about the exploration of social identity,” she explains. Victoria’s portraits challenge traditional representation. Encouraged by Xu Yang to turn the lens inward, she began painting herself, and later, others from the LGBTQ+ community. “I want to see honest paintings of transgender people and queer friends. People you don’t usually see in portraits.”

From day to day (2024) by Victoria Cantons

One of Victoria’s recent works encapsulates many of the themes that shape both her personal story and her visual language. A background of rich, visceral red frames soft, expressive pink flowers—forms that have been used for millennia as symbolic carriers of emotion and time, embodying the ephemeral nature of love, grief, and memory. Scrawled text reads, “Donnez-moi une chanson pour ma voix” ("Give me a song for my voice") and “If I have a voice I am someone”, asserting the act of claiming voice as both a personal and political statement. Binary code runs down the canvas like a digital rain, hinting at the modern idealisation—and coding—of femininity. “This is the idea of an ideal woman in code,” Victoria explains, “but the translation is simply: I AM LOVE.” The painting merges digital and organic, permanence and transience, in a quietly radical act of self-definition.

Untitled (The lesson will be repeated until it is learnt), 2024 by Victoria Cantons

An Artistic Dialogue

Both artists emphasize the importance of staying curious. “Explore different subject matter,” says Victoria. “Reflect your emotional state. Think about what you want the painting to say—how you want it to speak.”

This idea of painting as communication—between artist and subject, between two artists in a shared space—runs through their work. They exchange not just ideas, but values: independence, identity, and emotional truth.

Xu Yang recalls, “My mum told me: Be independent. Do what you like and don’t care what other people say.” That philosophy echoes throughout both of their practices.

A Shared Narrative, A Shared Future

For Yang and Cantons, collaboration is not just practical—it’s philosophical. Their studio is a crucible for two distinct but mutually enriching artistic voices. It’s a space where identity is explored, expressed, and shared. Their works present intrinsic, aesthetic and cultural value, bolstered by robust gallery representation and best in class art school accreditations.

Whether through Rococo dress, intimate self-portraits, or floral symbolism, their art invites us into a deeply personal yet universal exploration of selfhood. It’s a narrative that speaks not only to love and partnership, but to the transformative power of being truly seen.